The Map Is Not the Territory

Good product managers understand the map. Great product managers understand the territory. The best product managers build and understand maps so others can understand the territory.

Good product managers know the market, the product, the product line and the competition extremely well and operate from a strong basis of knowledge and confidence. - Ben Horowitz

Alfred Korzybski, a mathematician, presented a paper on mathematical semantics to the American Mathematical Society in 1931. In this paper, he introduced the phrase the map is not the territory. He later explained this as meaning words are not the things they represent. By their very nature, words are an abstraction (or a map) of the things they represent. And by definition, a map is a lower fidelity version of the territory it represents.

Note: This article uses the word “map” in a more general sense. I am not referring to a map of a physical landscape (although this could be the case for some products) but rather a map of human understanding.

In building products, we utilize maps all the time without realizing it. A common map is our view and understanding of our product market. Industries are incredibly complex and have international value chains. In today’s world, you can be the top expert in a domain and still use maps to understand how it works. These maps are simply abstractions, or lower-fidelity explanations, of how the real system works.

A common map product managers lean on is their understanding of the technology used to build their products. Product managers are not technical in many cases, but having an understanding of how the technology their team uses enables better communication and product design. This means product managers must understand the concepts behind their team’s technology stack without any formal training in that domain. This requires the product manager to build a map of how that technology works and fits together.

There are many other types of maps we use every day. Anything we use as a shortcut to understanding something more complex than we can hold in mental RAM would count as a map.

While these maps are extremely useful for us, we have to be sure to consider a few important things while we use them:

-

Maps can be incorrect without our knowledge (especially if we don’t understand the territory)

-

Maps don’t show the entire landscape (otherwise it would no longer be a map)

-

Maps are only valuable to a point for amateurs (only experts can utilize them to their full potential)

-

Maps are made by someone with an agenda (that could be ourselves or others)

All of these have great consequences for how we utilize maps in building products. Maps can be tremendously helpful in building a great product. Especially if you don’t need to understand the full terrain. The key to using a map effectively is knowing how and when to work around these limitations.

Maps Can Be Incorrect Without Our Knowledge

Remember that all models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful. - George Box

All maps are going to be wrong in some places. If they weren’t, they would cease to be a map and would be the territory they represent. This means we should always be on the lookout for places where our map is wrong, and be proactive about making changes to ensure it doesn’t hurt the way we build our products.

The biggest place this can bite you is mistakes in your map of how your target market operates. Having mistakes in your understanding of a process, a legal requirement, or even just how much time your users have to use your product can be detrimental to what you are building. Without constantly revisiting these maps you will, at best, build something that is not needed and, at worst, build something that causes harm to your customers or their customers.

Unfortunately, the feeling of being right and being wrong is exactly the same until you notice you are wrong. This is the same with your map. You have no reason to assume it is wrong until someone tells you otherwise.

If your map is wrong, big iterations will be costly. Work in short cycles and search for continuous customer feedback to revise your map. These small adjustments will ensure you are headed in the right direction and are building something your customers need and will use.

Maps Don’t Show the Entire Landscape

There are parts of the map which cannot (and should not) be reduced to a lower fidelity version. Your job as a product person is to know the landscape enough to make decisions about which parts of your landscape should not be reduced.

Imagine you are taking a bike ride and you are headed up the side of a mountain. The map says the road travels straight up the mountain, only a 2-mile drive. You assume this means it has a specific grade (incline) and ensure it fits within your training regimen. But, when you actually get to the base of the mountain, it is a windy road that totals 5 miles and has a much lower grade throughout. This may not be a big deal if you are riding for enjoyment (and may be referred to as the shorter, harder ride). However, if you were counting on that hard and fast incline, you are out of luck.

This is the same in building products. Removing the fidelity from the map can be very helpful in simplifying the landscape, getting people to understand the big picture, and helping plan courses without worrying about small details. But, if you accidentally reduce the fidelity of your map in the wrong places, the consequences can be great.

Brushing over what appears to be a small detail to you, could be a completely unusable product to your customers. It could also mean a completely misunderstood landscape for your team members.

It is your job to understand the landscape of everything around you enough to know when it is appropriate to reduce the fidelity, and when it is not.

Maps Are Only Valuable To a Point For Amateurs

“A model might show you some risks, but not the risks of using it. Moreover, models are built on a finite set of parameters, while reality affords us infinite sources of risks.” - Nassam Taleb

If you are an amateur in part of the domain in which you work, you are not going to work as effectively as you could. This means that most of your job as a product person should be learning and understanding the problem, and how the industry surrounding the problem works. Becoming an expert in your domain helps you understand not only what risks the model shows, but what the risks are in using that specific model.

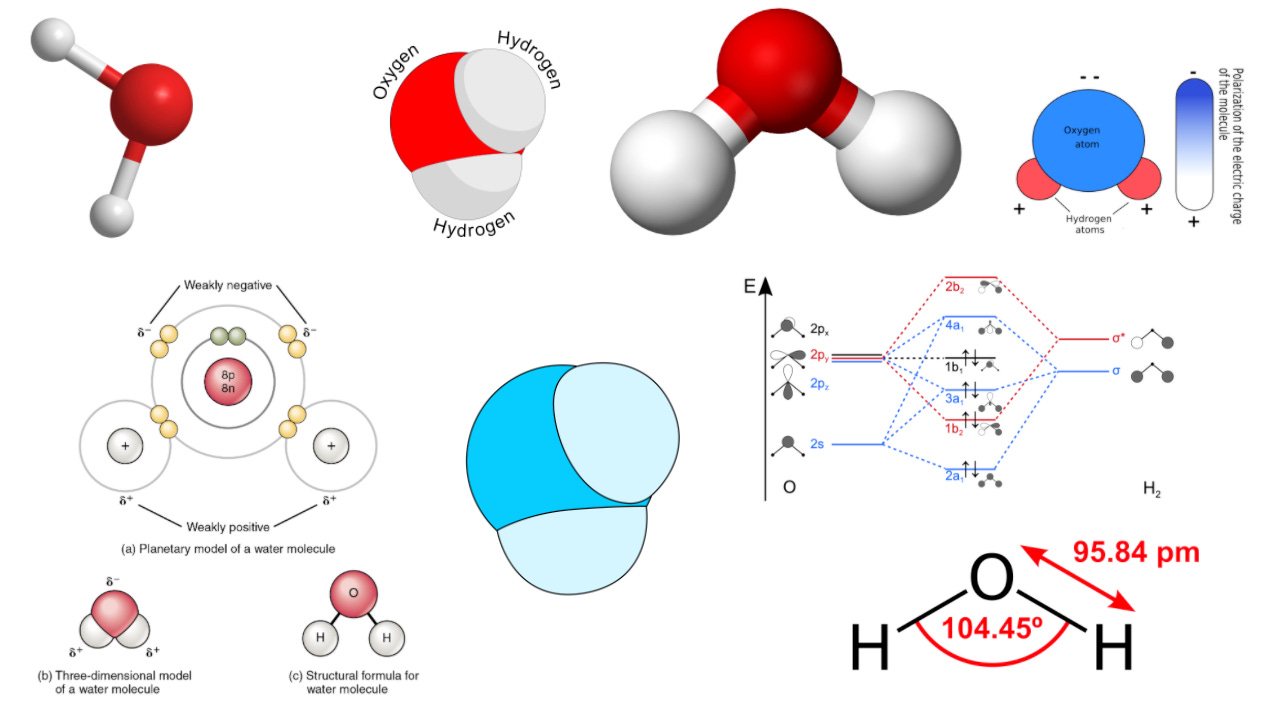

In chemistry, many different maps are used to understand the territory. The way we visualize molecules is a great example. Most visualizations of a water molecule look something like this:

A novice might assume this is what the actual molecule looks like and wonder why water is blue instead of red. However, the expert would know this model is only useful in understanding the relative size, distance, and angles between the individual atoms. They would combine this with many other maps to get a better understanding of what a water molecule looks like:

Find trusted experts, they can use your map more effectively and help you build your map (and potentially combine it with other maps) to be used by others most effectively. The most important thing in using expert resources is to internalize what they are telling you. As a product person, you should be _ the _ expert on your team about the customer, the industry, how the product works, and what problem you are solving. Without being this expert, your maps will be meaningless and won’t be valuable to anyone on the team.

Maps Are Made by Someone With an Agenda

When you build a map of the problem space you are working in, there are always assumptions that will be made. These assumptions are what lead to problems like the ones listed above. In order to avoid these assumptions, you need to know who is working on the map and what their motivation is.

Whenever we are building a map of a territory, there is some motivation to do so. We are likely trying to understand something complex in a way that is useful to frame a problem. We may be trying to find a place to use a solution within that domain. We may be trying to convince ourselves that something will work within the landscape when data may be saying otherwise.

Knowing the motivations of the map-maker will ensure you can look objectively at the map and see where mistakes or assumptions were made. You can see why parts of it were lower-fidelity and ask why. You can understand how the problem was mutated in order to fit a model that is easier to reason with and build products within. Knowing the landscape well enough to look for these inconsistencies can help you understand what it is you need to focus on as a product person when you are building.

Maps are an incredibly helpful thing to use when building products and reasoning about complex domains. Sometimes these maps are simply a diagram of a system. They may be a mental model of the way an industry works. It could be the product vision and strategy documents you create to keep your team marching to the same drum. All of these are maps of a territory, made to take something infinitely complex and distill it down to something more useful.

But remember, the map is not the territory. The reality may be something simpler, it may be more complex, it may be completely different than what is represented in the map. Build maps that are useful for you and your team. Look objectively at the maps built by others. And be willing to constantly revise your maps to adapt to new information.