Removing Product Friction Isn't Always Good

The main goal you have in building a product is to reduce friction from a process/problem your users currently experience. You aim to improve their lives. You unlock the ability to do things that were not possible without your products. This level of removing friction doesn’t happen accidentally. Your entire job as a product manager is to make impossible things, possible.

Building products is all about friction.

During the discovery phase you are identifying points of friction by talking to customers and finding out what parts of their workflow sucks.

During the design phase you are highlighting points of friction by creating mockups and design specs that showcase the new, frictionless workflow.

During the building phase you are testing the removal of friction by getting users to test your product and provide feedback.

Then the cycle starts over again as you interview customers who are using your products in their day-to-day work.

I was thinking about how this applied to my products and two questions came to mind:

-

What is product friction, really?

-

Is it possible to remove too much friction from a product? What happens if you do? (Spoiler: You can definitely remove too much friction, and your users are the ones who will suffer because of it.)

What really is product friction?

The best definition I have seen for product friction comes from an essay by Sachin Rekhi called The Hierarchy of User Friction.

“[Product Friction is] anything that prevents a user from accomplishing a goal in your product.” — Sachin Rekhi

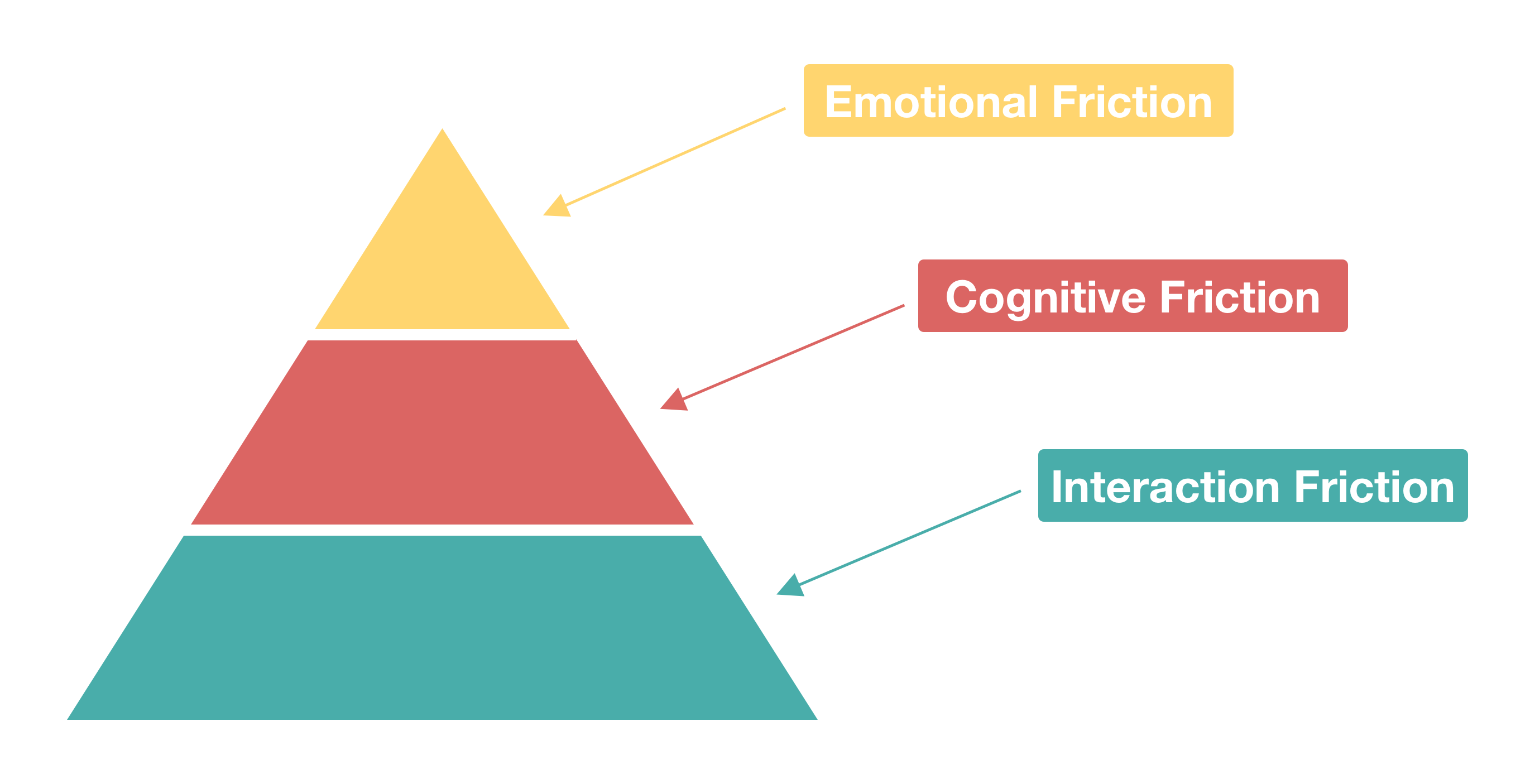

In his essay, Sachin lays out the three main types of product friction: interaction friction, cognitive friction, and emotional friction.

Image Credit: Sachin Rekhi

Understanding these three types of friction is paramount to identifying and reasoning about what the right amount of friction is for your product, and when removing more friction would actually hurt your users.

You should definitely read Sachin’s post in full. He dives deep into why these are the three categories of friction and how they apply to building products, but, for now, a working definition of each will suffice:

Interaction Friction: Friction a user experiences when interacting with your product’s interface. This type of friction is centered around the UI provided by your product. This could be a GUI, an API, or a more tangible good. Whatever your users interface with to use your product falls into this category. While this is important, it is typically not the place people end up removing too much friction.

Cognitive Friction : Anything that increases the total amount of mental effort being using in working memory. Features or workflows that make your users think harder or longer about how to accomplish their goal fall into this category. This could easily be impacted by interaction friction, but doesn’t only include UI elements.

Emotional Friction: Emotions your users feel that prevent them from accomplishing their goal. This type of friction can be caused by your product, but many times this friction originates outside your product and it is your job to help alleviate it. Past experiences and the perception of others are main causes of emotional friction for your users.

Removing too much friction isn’t always a good thing

While removing all three types of friction is one of your primary jobs as a product manager, there can be too much of a good thing.

Removing too much friction from a product can have disastrous consequences. From hurting your users, to affecting other parts of your product, to collapse of an entire system, sometimes friction is what holds everything together.

Hurting User Safety

Your users want to accomplish their goal with your product is efficiently as possible, within reason. Most of your users are unlikely to offer up personal safety in exchange for any decrease in process friction.

Case Study: Robinhood

While you don’t want to optimize your product for the “lowest common denominator” or your least savvy user, you do want to make sure they can use your product safely.

Robinhood, a financial investments app, has significantly reduced the friction for buying and selling stocks, ETFs, and options. They have reduced it so much that you don’t even need to have a large sum of money to buy stock in your favorite companies because you can purchase fractional stocks.

The workflow is simple. Download the app. Sign up for an account. And viola! You are ready to start buying and selling. “Making your money work harder”, as the Robinhood slogan says.

People are raving about Robinhood. In fact, they just raised another large round of capital to continue removing friction from the process of investing. But the success stories aren’t the experience shared by everyone.

Investing money is risky. It isn’t responsible for everyone to participate. And you don’t want to encourage people to put money into something that could hurt them eventually. Unfortunately, the reduced friction created in the Robinhood app has enabled that exact type of behavior. Users are placing larger sums into riskier, option-based investments without understanding the volatility and risks. [This has caused many to lose almost everything they have].

Robinhood is doing a great thing in reducing the friction for people to invest. It helps level the playing field for everyone and that is a good thing. But they should also be equipping people to play the game. Leveling the field isn’t enough when the users who need your product don’t even understand the game at all. Balancing the removal of friction while protecting users from themselves isn’t always easy, but it is critical. Especially when the stakes are this high.

Case Study: Zoom

Users don’t always need protecting from themselves. Sometimes they need protecting from others.

Zoom has taken the world by storm during the mass exodus from centralized office meeting rooms to decentralized, digital video calls. Zoom is the clear leader in the space.

One of the reasons Zoom has become so popular is their easy-to-use meeting client. You can join from your browser or the app. It takes one click to join the meeting. And even if you don’t have the link, the meeting ID is only 10 digits long. Zoom removed a huge amount of friction users experienced joining meetings on other platforms such as WebEx and GoToMeeting. They also simplified the in-meeting experience. Making the UI fast and responsive while eliminating the need to click in multiple different places to see attendees and the shared content.

All of this reduced friction introduced a problem as more businesses, schools, and courts started using it. People were guessing meeting IDs, joining meetings they weren’t invited to, and “Zoom-Bombing” everything from corporate meetings to elementary classes. While sometimes innocuous, many of these events resulted in users of the Zoom platform being harmed emotionally.

As a response, Zoom has changed 2 key product defaults: 1) Requiring a meeting password that is embedded in the link and 2) forcing the meeting host to admit all users to the call explicitly. Both features add friction to the product, not eliminate it. And while it can be a pain, that is a good thing. Adding friction in key parts of the product likely wasn’t on the roadmap for Zoom , but responding to issues and adding it in was the right decision.

Impacting other parts of your product

Sometimes you may want to introduce friction in one part of your product to remove friction from and highlight other parts of your product. While we like to see each feature independent of others, most of the time the friction removed in one feature can impact the friction in another. As a product manager, you have to decide which features are your highest value and most important. These should be as frictionless as possible even at the cost of increasing friction in another place.

Case Study: Apple and the App Store

Apple has been feeling the heat lately due to their handling of some high-profile apps and their removal from the app store. This has sparked a wave of conversation about the App Store, Apple themselves, and why they can maintain such a tight control on the only way to install apps onto the most common smartphone in the world.

This all goes back to the value proposition Apple is actually selling with the App Store: Ease and Security.

The App Store isn’t the only way to install apps on an iPhone because Apple wants to do all the extra work of verifying every app that could get installed on an iPhone. It also isn’t the only way to install apps on an iPhone because they want to take 30% of all In-App Purchase revenue (though it may seem like it). The main reason why you can only install apps on an iPhone through the App Store is because Apple is removing cognitive and emotional friction.

There once was a time when there were many app stores for Blackberry and Android devices. You would have to determine which was the most reputable, cross your fingers that the app was any good, and hope it wasn’t some piece of malware about to steal all your data once downloaded. This emotional and cognitive friction was a priority for Apple to remove.

The App Store removes all cognitive and emotional friction from installing an app on an iPhone. You know it will be safe, you know where you are getting it from, and you know what other users have said about the quality of the app. As a result, Apple has increased friction (significantly) in other areas.

It is nearly impossible to sideload apps onto an iPhone and you can’t install third-party app stores from the App Store. This means things like Xbox GamePass aren’t available on the iPhone. To Apple, this tradeoff is worth it. They would rather maintain a low level of friction in the areas they see are most valuable to the majority of users at the expense of friction for the minority.

The collective system can fail

Last, but definitely not least, the removal of friction can cause entire systems to fail. When products are used at a large enough scale, removing friction can cause some to take advantage of the product in a way that wasn’t originally intended.

Case Study: Credit Cards

When credit cards were first introduced, they were intended to enable shoppers to purchase goods or services for which they didn’t have the funds readily available. They intended to pay back the debt in a reasonable amount of time or risked paying even more than they would have otherwise due to interest.

Over time, credit cards became ubiquitous. Every bank gave out high-interest credit cards to anyone who asked, and they asked for very little in way of proof that you were willing to pay back your debt.

Every person felt entitled to buy things they couldn’t afford and it changed the way we thought about wealth and money. The amount of held debt expanded in the 90s and early 2000s as consumers continued to utilize credit to buy things they had no ability to repay, such as cars and homes. Until it all came tumbling down in 2008.

Each individual person thought they were only impacting themselves. Their decisions to consume more than they could repay wasn’t affecting anyone else and it wasn’t that big of a deal… so they thought. This is a classical tragedy of the commons. Every person thinking it is no big deal that they consume more than their share until the whole system breaks down due to everyone acting in their self-interest.

While most of our products aren’t as ubiquitous as credit cards, it is easy to see that the removal of too much friction from the process in obtaining credit as well as utilizing that credit can cause disastrous outcomes.

How to determine when to remove friction and when not to

There are 3 main ways I try to think about friction when making decisions about where to remove friction and where to introduce it: 1. Go back to your product goals, 2. Define your biggest differentiator, 3. Think like your users.

1. Go back to your product goals

Assuming you have your overall product vision and goals in place, you should be using these to determine priority of removing friction. You don’t want to run around with a proverbial machete, removing friction from everywhere in your users workflow. Instead, think of removing friction more like a surgeon, carefully cutting and removing to ensure a balance between removing the bad parts while optimizing the whole.

2. What is your differentiator?

Knowing what your biggest differentiator should help you find places that you want frictionless. This should also help you pinpoint where you need to be cautious in removing too much friction. Keeping the parts of your product that are your key differentiators in your mind as you carefully cut friction will ensure you don’t sabotage yourself by cutting in a place you shouldn’t. Think like the Apple team does when deciding how users get apps onto the iPhone. You have to ignore some feedback to keep your differentiator perfect.

3. Think like your users

There are 3 types you users you want to be able to channel:

-

Your most knowledgeable user: These users know exactly how your product works and understand all the risks. They can handle some responsibility as long as it doesn’t compromise your next user…

-

Your least knowledgeable user: This user has no idea what to do in your product and may get themselves in trouble. Don’t remove the friction so much that they miss the bumpers and fall into the gutter.

-

A nefarious actor: What would happen if a bad actor could exploit your most frictionless feature? How would they do it? What would the result be? This can be hard to imagine, but trying to put yourself in these shoes can prevent lots of headaches downstream.

Eliminating friction from your product is critically important to building something users want. Most of the time, you want to focus on how you can remove as much friction from the product as possible. However, while you are working on removing product friction, be sure to keep in mind that not all parts of your product are created equal and sometimes removing friction can cause more harm than good.

What are some other examples of products that removed too much friction? Post them in the comments below and I will share them on Twitter!